Discuss

the interaction of cultures in the area of Hadrian’s Wall .

Hadrian’s wall . Over time these would interact in different

ways eventually becoming more comfortable in each others presence such that

Roman Soldiers (or at least soldiers of the Roman Army (as ; not all soldiers in the Roman army were

Italian. Inscriptions from Arbeia

include Pannonians, Spaniards, Gauls, Moors and Syrians – as well as Italians)

would be setting up Altars to British gods, such as that set up to

Antenociticus at Benwell.Hadrian’s Wall was not

uninhabited when the army arrived there.

Indeed the wall cut across the territory of the Brigantes at its western

end (Huskinson, 2000 p64)[ii]. So the establishment of permanent bases in

tribal territory would have forced interaction between the natives and the

army. As the wall bisected tribal

territory there may be a stronger argument for its role, at least early in the

period when Roman Units were still stationed to the north, as a means of

controlling, and thereby taxing trade, rather than as a purely defensive base

although its numerous guard positions and forts do not rule this latter

function out. The presence of the vallum

to the south of the wall has been interpreted as evidence of local interaction

or encroachment upon the wall (Video 2) although this interpretation is one of

many it is worth noting as it represents a plausible reason for changes to the

structure of the wall over time as a result of interaction between civilian and

military needs.Regina Hadrian’s Wall . Factors that shaped culture in the area would

have included the make up of the army units stationed there, the nature of

local people and the interaction between soldiers and civilians. Evidence of religious and cultural practice,

including the classical art used to depict local gods Over time relationships

in the area would have changed assimilation of local customs by the army and of

ex-soldiers into the local settlements would likely have increased the cultural

homogeneity of the area. At times, such

as during the period of Antoninus Pius when a new northerly frontier was set at

the Antonine wall, the garrison of the wall may have been relatively small and

therefore interactions between locals and the army limited. Although literary sources are scarce, this

area is relatively rich in archaeological evidence but this remains open to

some interpretation so it is not possible to be certain how well the combined

Roman British and even Caledonian populations intermingled, some degree of

acculturation can be reasonably concluded from the archaeological record. One important question remains however and

that is just how permanent were the changes brought about by the presence of

the Roman Army in the area? Video 2

points out that within 50 years of the departure of the army a great deal of

its infrastructure – roads, bridges, plumbing – had disappeared. This disappearance should not be taken, I

believe, as an indication that the Roman effect on the culture of Britain Milton

Keynes Milton Keynes Oxford University Press, Oxford

Aeneid 6.791-800 - How and why does Virgil promote

Augustus in this passage?Rome Gaul and Augustus’s own victory

(or at least Agrippa’s) over Marcus Antonius, this affirmation puts into the

minds of the listener the image of a great General.Holland Holland Actium

the bloodshed of the civil war ceased but the memory had not disappeared

overnight, it is not likely therefore that Virgil would have considered

criticising Augustus. However another

view may be taken here. The memory of the civil war of the 30s and 40s BC may

have made Virgil truly glad for the return of peace that Augustus’s triumph

represented. In other writing’s, Virgil

had depicted the miseries of those dispossessed by the break down of civil

society (Holland Holland ,

T (2003), Rubicon The Triumph and Tragedy

of the Roman Republic , Abacus, London

Word Count 1661 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Discuss

the interaction of cultures in the area of Hadrian’s Wall .

Frontier is defined by

the Oxford English Dictionary in more then 1 way. It may be ‘the frontline or foremost part of

an army’ or the ‘part of a country which fronts, faces or borders on another

country’ or ‘that part of a country which forms the border of its settled or

inhabited regions’. All of these

definitions are relevant to this discussion as the variety of definitions is

matched by a variety of different inhabitants, cultural practices, types of

settlement and trading patterns around Hadrian’s wall . Over time these would interact in different

ways eventually becoming more comfortable in each others presence such that

Roman Soldiers (or at least soldiers of the Roman Army (as ; not all soldiers in the Roman army were

Italian. Inscriptions from Arbeia

include Pannonians, Spaniards, Gauls, Moors and Syrians – as well as Italians)

would be setting up Altars to British gods, such as that set up to

Antenociticus at Benwell.

The different

components that affected culture in the area can be broken down into a number

of categories and sub categories. Firstly

consider the nature of the military and civilian inhabitants of the area. These may be categorised in terms of members

of the Roman Army whose commanders would likely belong to the Roman Elite or

Equestrian classes and the soldiery who may be legionary Roman Citizens or

non-Roman Auxiliaries. Already there is

a great degree of heterogeneity within this group that is further complicated

by the fact that many of the soldiers, such as the Thracian Longinus Sdapeze

(Huskinson, 2000 p54)[i]

originated from outside the Italian peninsula.

Despite this heterogeneity of origin, long service with the same comrades

and in the same units, often in the same area, together with standard military

law and training plus allegiance to the emperor made the soldiers culturally homogenous

in outlook at least during our period.

In the area of the

frontier the military would have interacted with local civilians. The Roman military was relatively well paid

and large numbers of troops would have provided a market for civilian traders,

indeed in the frontier area a specific trading pattern may have developed to

service the military camps. The

gatehouses and vallum of Hadrian’s wall appear to have been designed to control

passage between Roman and non-Roman territory (though literary evidence is

scarce) thus the wall may well have been used by the Romans as a means of controlling

the passage of traders form North to South.

It should also be noted

that the area around Hadrian’s Wall was not

uninhabited when the army arrived there.

Indeed the wall cut across the territory of the Brigantes at its western

end (Huskinson, 2000 p64)[ii]. So the establishment of permanent bases in

tribal territory would have forced interaction between the natives and the

army. As the wall bisected tribal

territory there may be a stronger argument for its role, at least early in the

period when Roman Units were still stationed to the north, as a means of

controlling, and thereby taxing trade, rather than as a purely defensive base

although its numerous guard positions and forts do not rule this latter

function out. The presence of the vallum

to the south of the wall has been interpreted as evidence of local interaction

or encroachment upon the wall (Video 2) although this interpretation is one of

many it is worth noting as it represents a plausible reason for changes to the

structure of the wall over time as a result of interaction between civilian and

military needs.

Evidence of cultural

interactions can be found in different cultural practices in the area. These have been classed as Celtic, Classical

and Imported non Classical (Salway p666)[iii]. Archaeological evidence of these practices

mixing is widely available in the area.

Already mentioned is the altar set up by a Roman Soldier to

Antenociticus which is evidence of acceptance of local customs by the occupying

forces, although the representation of Antenociticus is clearly Roman. Although the Romanization of local gods is

not uncommon as is represented by the classical representation of the Celtic

Goddess Brigantia from near Birrens (Plate 4.31) there are also examples of

clearly Celtic symbols in Roman settings such as the horned warrior god from

Maryport (plate 4.33). This evidence of

cultural interaction should however be tempered by examples of clearly Roman

practice such as the following of the Emperor cult and the worship of Mithras (Mithras was not a British god, and his worship was only

open to initiates, so it did not represent cultural interaction with the local

population. It did however, show the

inclusive nature of the Roman pantheon when an eastern god could become the

object of devotion among Roman soldiers) nevertheless the evidence of even high

ranking Romans allying themselves with local gods is significant in that it

shows that over time members of the army becomes accultured to the area so that

cultural interaction is not just one way.

Non classical imported cults are also in evidence such as the altar at Corbridge

, set up by a centurion, dedicated to Jupiter Dolichenus, to Caelestis

Brigantia (a North African deity combined with a local goddess), and to Salus.

The nature of

Settlements is a further factor or symptom of cultural interaction. Whilst army officers brought their wives with

them to the area, Roman soldiers below the rank of centurion were not allowed

to marry during their service, until the Severian edict of 197, nevertheless many

acquired ‘wives’ and families who effectively became camp followers in nearby

settlements not far form the military bases.

There is a lot of tombstone evidence of such marriages between soldiers

and local women for example the tomb of Regina

To conclude it should

be noted that numerous interactions between the Roman army and local populations

would have occurred in the area around Hadrian’s Wall . Factors that shaped culture in the area would

have included the make up of the army units stationed there, the nature of

local people and the interaction between soldiers and civilians. Evidence of religious and cultural practice,

including the classical art used to depict local gods Over time relationships

in the area would have changed assimilation of local customs by the army and of

ex-soldiers into the local settlements would likely have increased the cultural

homogeneity of the area. At times, such

as during the period of Antoninus Pius when a new northerly frontier was set at

the Antonine wall, the garrison of the wall may have been relatively small and

therefore interactions between locals and the army limited. Although literary sources are scarce, this

area is relatively rich in archaeological evidence but this remains open to

some interpretation so it is not possible to be certain how well the combined

Roman British and even Caledonian populations intermingled, some degree of

acculturation can be reasonably concluded from the archaeological record. One important question remains however and

that is just how permanent were the changes brought about by the presence of

the Roman Army in the area? Video 2

points out that within 50 years of the departure of the army a great deal of

its infrastructure – roads, bridges, plumbing – had disappeared. This disappearance should not be taken, I

believe, as an indication that the Roman effect on the culture of Britain

[i] Huskinson,

J. Hope, V. and Nevett, L. (2000) AA309

Block Four Roman Britain, The Open University, Milton

Keynes

[ii] Huskinson, J. Hope, V. and Nevett, L.

(2000) AA309 Block Four Roman Britain,

The Open University, Milton Keynes

[iii] Salway, P. (1985), Roman Britain, The Oxford University Press, Oxford

The direct reference to Augustus in this

passage clearly ensures that there is no possibility in confusing the target of

the praise within the passage, there is no effort made simply to allude to the

Princeps. In trying to understand how

Virgil is promoting Augustus, it is possible to see overt and direct reference;

however there is also subtler praise within the text. We cannot be absolutely certain why Virgil praises

Augustus because he doesn’t tell us, although by looking at the context within

which it was written we can make an educated guess.

Firstly how does Virgil praise Augustus? Overtly, Augustus is praised as the promised

one, as though chosen by fate to bring glory to Rome Gaul and Augustus’s own victory

(or at least Agrippa’s) over Marcus Antonius, this affirmation puts into the

minds of the listener the image of a great General.

Further overt praise is made by alluding to the greatness

of a future promised under Augustus – promises of a new golden age and of

empire stretching beyond the world into the zodiac. This latter mention of the zodiac again

subtly emphasises, by reference to the heavenly sphere, Augustus’s

divinity.

Overt, but subtle praise is used when Virgil talks of the

trembling of the Caspian realm and of the Crimean country. This alludes to both the power and military

prowess of Augustus and even to peoples beyond the Roman world having heard of

this power. In Roman society making

one’s enemies tremble at the sound of your name would have been a sign of

greatness.

Why did Virgil praise Augustus? There are number of possible and plausible

explanations. The first being that he

may have been paid to do so (Goodman, 2006, p181)[1] –

or at least have been given significant patronage. Augustus was keen to encourage the propaganda

of his legitimacy, to link with Caesar and to be seen as a great soldier. He was careful therefore to patronise the

poets who were able to provide this image on his behalf. A second possible reason why Virgil was keen

to praise may have been through fear.

During the Triumvirate Augustus had clearly demonstrated a ruthless

streak in the years following Phillipi (Holland Holland Actium

the bloodshed of the civil war ceased but the memory had not disappeared

overnight, it is not likely therefore that Virgil would have considered

criticising Augustus. However another

view may be taken here. The memory of the civil war of the 30s and 40s BC may

have made Virgil truly glad for the return of peace that Augustus’s triumph

represented. In other writing’s, Virgil

had depicted the miseries of those dispossessed by the break down of civil

society (Holland

In reality it is extremely unlikely that

Virgil would have heaped the praise upon Augustus for one reason alone. It is more likely that Virgil’s motive was

the outcome of a number of these reasons.

[2] Holland ,

T (2003), Rubicon The Triumph and Tragedy

of the Roman Republic , Abacus, London

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

Compare and contrast

the accounts by Mark Noll and Alexis de Tocqueville of the role of religion in

political life in the United States in the early nineteenth century. How

important was Christian identity to the development of American nationhood by

1865?

The extracts by Noll

and de Tocqueville are separated by more than 150 years. Whilst Noll is writing with the benefit of

hindsight he is required to use secondary sources whereas de Tocqueville writes

from personal experience. These

different viewpoints affect the different authors accounts. In this essay I will deal firstly, with the

general context of the two accounts before looking at specific differences and

the conclusions drawn by the two authors.

I will then go on to give my own interpretation of how important

Christian identity was to the development of nationhood up to the end of the

Civil war in 1865.

Writing in different

times and through different witnesses gives the accounts of Noll and de

Tocqueville quite distinct differences.

Noll, has the advantage of the use of a wide range of statistical data

that was not available to de Tocqueville as well as good accounts from

contemporary participants in the events recorded. De Tocqueville, on the other hand has a more

limited view, in time and space, of personal experience but has the advantage

of writing from direct knowledge of ongoing events. These different vantage points may well

account for the different emphasis placed on Christian denominations by the two

authors. De Tocqueville, with his

Catholic French background, spends a considerable amount of time reviewing the

democratic credentials of Roman Catholicism within the United States. He notes the differences in its practice as

an instrument in support of democracy in America rather than tyranny as in

Europe. De Tocqueville concentrates on

Roman Catholicism but acknowledges that there are a wide range of Christian

sects in America, noting that Roman Catholics are in a minority that is

protected by, and therefore supports the constitutional separation of church

and state.

In contrast to de

Tocqueville, Noll highlights the massive expansion of Evangelicalism through

the Methodists and Baptists from the late 18th century. Noll acknowledges that Roman Catholics are a

growing minority but highlights that they represent mainly an immigrant

population whereas Evangelical Protestantism expands from within through

missions to the expanding territories and supported by improved industrial methods

and communication. Unlike de

Tocqueville, Noll is concerned not only to record the importance of religion in

the United States but also to explain the reasons for the growth of

religiosity, noting that all denominations grew in adherents from the Revolution

to the Civil War but that the Evangelical sects grew massively.

Both writers link the

importance of religion in the formation and maintenance of democracy although

the emphasis each places on religion is different. De Tocqueville holds religion to be

‘indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions’ (de Tocqueville

xxx)[1]

whilst Noll identifies the rise of Evangelicalism to be a result of democracy

that results from the revolutionary war.

Noll identifies four possible reasons for the growth of religiosity but

seems most drawn to the argument that the Revolution caused social dislocation

that then required a period of social reconstruction within which the Methodists

and Baptists seem to have found a niche.

The Evangelical’s ideology, Noll claims, of self-selection of leaders,

of grass-roots organization, of the rejection of mediation to achieve salvation

and in particular of individual interpretation of scriptures, matched neatly

the post revolutionary Zeitgeist. The

revolutionary war, claims Noll, sanctioned liberal, democratic, populist and

individual constructions of liberty as well as arousing popular principles and

eliminating deference to authority. Noll

quotes Wood in support of his argument for the reasons of the expansion of evangelicalism

that churces in America had to construct revolutionary forms of Christianity or

decline.

As I have already said

both de Tocqueville and Noll identify religion as important to the development

of American democracy. They take

different viewpoints however. De

Tocqueville is concerned to observe that which he can see around him. Noll has a wider view and draws on the

scholarship of others as well as primary source material not only to comment,

as de Tocqueville, but to explain.

Noll’s concludes that the rise of evangelicalism is the result of common

people choosing to ‘shape the culture after their own priorities rather than

the priorities outlined by gentlemen’ (xxxx)[2]

whereas de Tocqueville sees religion as central to the maintenance of democracy

rather than shaped by it.

The Puritans were

amongst the earliest settlers of the American colonies and although a number of

their beliefs and practices such as support for the concept of pre-destination

the need for experience of personal revelation, were superseded, particular

with the rise of the Evangelicals and other sects such as the Quakers, they

have left a legacy in the American cultural memory. Chidester (2000, p425)[3]

recounts the early Puritan settlements of Massachusetts of which the leaders

considered themselves to be not only refugees from the oppression of the

religious establishment but also the founders of a new Zion. This concept of Zion on the American

continent remained strong and was reinforced in the early nineteenth century by

continued religious revivalism and is evident in the ideology of the Church of

Jesus Christ of the Latter-day saints. Other

Puritan legacies that out-lasted the Puritans themselves included the belief,

expressed by the Evangeilcals in the nineteenth century, that the Bible was the

final divine revelation and therefore source of authority. Additionally the

consepts of religious freedom that became part of the US constitution can be

traced to the Puritan’s own desire to protect their religious freedom. To the puritans can be traced, also, the

‘Protestant’ ethics of self-reliance and hard work (whether or not these are

truly ‘protestant’ can be argued see AA307 CD3).

Whilst all of these

characteristics feed into the development of the American nationhood into the

nineteenth century, the Puritans belief in Theocracy rather than democracy and

strict hierarchy did not survive. By the

late eighteenth century the political upheavels that led to the revolutionary

war created a new enlightenment influenced emphasis on individualism,

democratic participation (for whites), anti-authoritarianism and freedom from

religious dogma that contributed, as noted above, to a great expansion of

Christian congregations, particular of evangelical sects. These sects would play an increasingly

important role in the development of national identity as they grew, though it

must be noted that they were not a coherent grouping.

The American revolution

caused a social dislocation, as already mentioned, that contributed to the

expansion of evangelicalism. The

revolutionary leaders influenced by the enlightenment and looking across the

Atlantic were concerned to ensure freedom from religious tyrrany and therefore

ensured freedom from religion by allowing freedom for religion thus assisting

more individualistic religions to flourish from 1776 onwards.

The ownership of slaves

was easily justifiable in an ideology that accepted everyman should bear his

god-given role that was characteristic of Puritan thinking. However, after the revolution, where whites

declared themselves to be free, it was difficult to make a coherent argument

for slavery, although some tried. The

Presbyterian minister Charles Colcock Jones, for example, was one of many that

preached that slaves should honour their masters as they had been placed in

their position by God (Chidester, 2000, p 437).

The growth of evangelicalism from the late eighteenth century not only

challenged these views but also appealed to the slaves themselves so that

Christianity was spread throughout the population of America even if different

sects had widely different viewpoints.

The missionary zeal of the evangelicals, facilitated by

industrialisation, territorial expansion and improved communications meant that

their individualistic, democratic, anti-establishment ideology became

widespread. In particular it captured

the post revolutionary Zeitgeist. As mentioned earlier, Noll pointed out that

the revolutionary war sanctioned the same liberal, democratic, populist and

individual constructions of liberty that the evangelicals espoused.

Largely as a

consequence of the expansion of all Christian denominations during the first

half of the nineteenth century American society was strongly moralistic

(Wolffe, 2008, p15)[4] in

outlook with a particular stress on family values. Evidence for this is seen in the wide range

of social concerns championed by the evangelicals that include temperance,

prison reform and a range of other issues as well as abolition. By the middle of the nineteenth century, there

was a strong religious tone to American public life. In spite of this there was conflict between

denominations, as can be seen in the anti-catholic riots in Charlestown in

1834, as well as between economic and political interest groups that were

concerned to use the scriptures to justify the iniquities of slavery.

A significant

consequence, noted by Wolffe (2008, p15) of the ‘strongly religious tone of

American public life’ was that when Civil War broke out both sides considered it

to be a holy war with God on their side

I have shown here that

Christianity was a major force in the development of American nationhood to the

middle of the nineteenth century – so much so that we leave two sides fighting

a holy war against each other. Having

said that there were also other factors at play during this period. Politically the revolution itself provided

the ideology and space for the expansion of the variety of Christina

denominations, particularly for the Methodists and Baptists. I would argue that without the revolutionary

mindset that cast off authority, declared freedom for religion and set in train

a democratic mindset there may not have been the same explosion of religiosity

that we see. Although most of the

Word Count 1661

Chidester,

D. (2000), Christianity, Penguin,

London

[1] Quoted in

Wolffe, J (2008), AA307 Religion in

history: conflict, conversion and coexistence Study Guide 3, The Open University [3] Chidester, D. (2000), Christianity,

Penguin, London

[4] Wolffe,

J (2008), AA307 Religion in history:

conflict, conversion and coexistence Study Guide 3, The Open University

Compare the role that different aspects of

US power might play in

realising the USA US USA USA USA again took

up an isolationist position, which contributed significantly to the failure of

the League of Nations as a security

institution. Its entry into world war

two and its subsequent multi-lateral engagement in the international system

have brought it to pre-eminence. The

position of the USA has come about as a result of its victory in world war two

and its then military (until the mid 1950s it was the only nuclear power) and

economic strength vis a vis its strategic partners in Europe after 1945 and its

eventual ‘victory’ in the Cold War as a result of the economic collapse of the

USSR. From a realist perspective, it has

achieved its position because it has ‘imposed [its] will on lesser states

and…because other states have benefited from and accepted [its]… leadership’

(Gilpin, 1983, p 145.)[2]USA US USA USA USA USA USA USA USA US USA USA Europe

and beyond has been seen as some (Bromley, 2004, p147)[5],

as a compelling source of US power reshaping the world (Gramsci, 1971, p317)[6].

Given the very different social systems in Europe Americanism is only part of

the story accounting for the USA Anderson USA USA Daytona Beach , Florida US USA US United States USA USA France , Germany Russian and China deprived the USA US USA USA US US

public opinion was horrified at events in Chechnya

in the 1990s and yet the costs of using military or economic power against Russia were too high for the USA USA Pearl

Harbour , “so, too, should this most

recent surprise attack erase the concept in some quarters that America USA

still has the world largest economy, the states-system is multi-polar with the

EU and Japan already as

major liberal competitors to the USA

and new regional economic powers developing in China ,

Russia and perhaps India USA US South East Asia the application of military power is

inconceivable except as providing regional security guarantees to liberal

capitalist states. In Europe, continued

involvement in NATO and the application of soft power to encourage eastward

expansion of NATO and the EU also helps to neutralise regional pretensions to

leadership of France and Germany Russia , and China the USA Russia , China

and the USA China , Russia and perhaps other are uncomfortable with

the USA ’s unipolar moment

and will try to hasten a multipolar world, the USA USA ’s actions in Iraq USA U.S. US

policy in Iraq Iraq USA to achieve its foreign policy objectives

at….low cost ….depend in a large part on whether other powers are inclined to

support or oppose US USA USA USA USA cannot

control all the threats to these public goods (Bromley, 2004)[17]

In most cases, therefore, it will be in the interests of other states to work

with the USA USA USA USA U.S.

[1] Brown, W. (2004) A liberal international

order, in Bromley. S et al (2004) (ed) ‘’Ordering the International: History,

Change and Transformation’, London and Sterling Virginia Cambridge US Power and Strategy After Iraq London London

and Sterling Virginia London ,

Lawrence

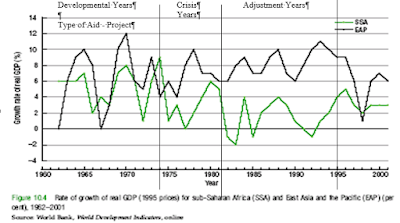

Graph 1 – Rate of growth SSA compared with East Asia and

Pacific - note lack of high growth during the adjustment years despite BWI

involvement (From Making the International p 312, original source World Bank)

foreign direct investment. Therefore, the deficit in availability of foreign

currency from trade has been made good mainly by foreign aid in two forms:

transfer payments on current account and loans on capital account. Therefore, throughout

Africa there is a high dependence on foreign aid.

USA

Abide by Kyoto deal

Don't abide by Kyoto Deal

EU

Abide by Kyoto deal

2,2 Preferred outcome to weak play

0,4 Nash Equilibrium

Don't abide by Kyoto Deal

4,0 Nash Equilibrium

-6,-6 Catastrophic Play

Figure 1 Matrix depicting

global warming as a collective action problem game between 2 actors

Analysing the game from the point of view of the EU, if the

USA acts tough and fails to abide by Kyoto, the EU’s best reply is to act weak

and abide as 0 is better than -6; if the USA acts weak and abides by the

agreement, the EU’s best reply is to act tough and not to abide as 4 is better

than 2. From the perspective of the USA,

if the EU acts tough and fails to abide by Kyoto, the USA’s best reply is to act

weak abide as 0 is better than -6; if the EU plays weak and abides by the

agreement, the USA’s best reply is to act tough and not to abide as 4 is better

than 2. These strategies show 2 Nash

equilibria (see figure 1) each cell indicating strategies that are best replies

to each other.

Part 2 b (728 words)

[1] Wangwe. S. (2004) The politics of

autonomy and sovereignty: Tanzania’s aid relationship, in Bromley. S et al

(2004) (ed) ‘Making the International: Economic Interdependence and

Political Order’, London and Sterling Virginia, Pluto Press in association

with The Open University

What was the role of technology in British imperial expansion?

The

British Empire grew in phases from English domination of the British Isles to

expansion across the Atlantic to trading posts in India and beyond and whilst

the gap in technological capability between the English/British and those areas

being colonised in these earlier phases of expansion was never as great as in

the late nineteenth century there were times when a gap was wide enough to make

a difference. Cromwell’s suppression of Ireland and Scotland through the

New Model Army, better American settler weaponry during King Phillip’s War and

James Cook’s banishment of scurvy with sauerkraut, not to mention innovations

in Naval Architecture and timekeeping, that allowed for his multiyear

exploration of the Pacific and the discovery and mapping of New Zealand and the

Eastern seaboard of Australia are all examples of imperial expansion enabled by

technology and should not be ignored. Furthermore, financial innovations

such as the establishment of the Bank of England as well as the Industrial and

Agrarian revolutions allowed Britain to outspend her continental opponents from

the 1700s onwards that would lead to her industrial and naval supremacy for

most of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries that gave her the strategic

space to expand her empire. From the 1750s extensive

use of copper sheathing to protect ships’ hulls assisted British dominance in

tropical waters. Military innovations in weapons and organization were

instrumental in expansion before 1800. The main

difference between these earlier phases of expansion and that of the nineteenth

century was that the technological gap widened significantly from the 1840s

onwards thus making expansion cheaper in lives and treasure and causing a rapid

acceleration that would not end until after the 1st World War when the new technology of air power was

deployed in the middle east in order to control the mandated territories.

What was

unusual about the 2nd half of the nineteenth century was the increasing

technological gap between Europe, particularly Britain, and the rest of the

world. This gap allowed for accelerated British imperial expansion, and

in this period expansion was not only made possible by the use of technology,

but was also rationalised by technology and the British came to distinguish

themselves from and claimed a superiority over others on the basis of their

mastery of science and technology. From the 1830s onwards, Headrick has

noted that technology allowed for a three-phased analysis of imperial

expansion. Firstly several technologies enabled the British to move

inland from their traditional trading posts to penetrate new territories.

The primary technologies employed were the flat bottomed, steam powered

river boats and the isolation of quinine as a malaria prophylactic.

Well-armed naval steam powered gunboats were instrumental in the defeat

of Chinese forces during the opium wars and the imposition of favourable, to

the British, terms upon the Chinese that not oly forced market penetration for

the opium trade but also led to the transfer of territory to the Empire.

Even

today inland communications within Africa are hampered by natural barriers,

disease and poor infrastructure and Africa had long been a European graveyard.

During Bolts 1777-79 expedition at Delagoa Bay, 132 out of 152 Europeans on the

journey died whilst Mungo Park's 1805 journey to the upper Niger resulted in

the death of all the Europeans. By the 1840s, Bryson and others had identified

the effectiveness of quinine and Laird’s 1854 expedition, following Bryson’s

advice on quinine dosage, lost none of the European members despite spending

112 days on the Niger and Benue rivers. Improved medical technology,

however only provided the means to stay alive, to travel flat bottomed steam

powered river boats were required. As Kubicek points out, these boats,

built in numbers for the Crimean War, were upgraded and distributed to various

stations where they both an instrument and symbol of Imperial control.

Kubicek cites the example of HMS Goshawk being used in 1887 to kidnap a local

ruler and palm oil merchant, Jaja of Opobo.

Once

territories were penetrated, control need to be wrested from the indigenous

population. This could be achieved by military force alone if sufficient

could be brought to bear or could be combined by weight of number, a population

could be overwhelmed by British Settlers, Ferguson’s ‘White Plague’. The

British diaspora to the colonies, though not new, was facilitated to a great

degree in the latter half of the century by a revolution in steamer traffic

resulting from the replacement of iron for steel as the preferred material for

ship and steam boiler construction and by from 1878 British usage of the Suez

Canal. The late century development of military capability, characterised

as ‘Maxim Force’ allowed for overwhelming firepower to be brought to bear

against those who resisted conquest – such as at the battle of Omdurman, though

it should be noted that in many clashes between the British invaders

and local peoples from 1875 that both sides had modern weaponry, the British

tended to have more of it and their factories could produce more.

Nevertheless, the South African War also showed, technological advantage

was being eroded through technology transfer to subject peoples. This transfer would eventually erode the

economy of empire and set limits to the expansion of the Empire.

Headrick’s

third analytical phase is that of consolidation – the bringing together of the

territories and their capabilities to a coherent whole. Consolidation is

one word but exploitation would be equally valid. New transport networks, rail

as well as steamship allowed for rapid communication and transfer of resources,

as well as armies to quell unrest. Modern mining technologies allowed

extractive industry, and provided a motive for imperial expansion, notably in

Southern Africa. New communications

technologies, notably telegraphs and undersea cables allowed for unprecedented speeds

of communication that gave London distinct advantages in getting markets data

and communicating to the imperial satraps thereby bringing the periphery under

greater political control. The ability to communicate rapidly also

allowed for effective troop deployment to keep the empire together. Telegraphy

was an effective in aiding suppression Indian mutiny as well as one that could

be used to provide the London financial markets with global news ahead of her

competitors. It even gave Britain a Strategic advantage over her European

rivals as Kitchener proved at Fashoda when he communicated to London via subsea

cable not available to his French counterpart or even more importantly during

World War One when German signals traffic to the USA travelled on British

Subsea cables, thereby bringing the Zimmerman telegram to light!

Headrick’s

phases approach to the analysis of the impact of technology on the expansion of

the British Empire is a useful one though in fact the reality is more muddles.

Certain technologies were employed in multiple of his phases. Technology

was not important solely in the later development of the Empire but it was

during the latter part of the nineteenth century when a distinct gap opened

between Europe and the rest of the world, particularly with Africa, that provided

for an acceleration of imperial expansion at a very low cost in lives and

treasure. This technological advantage would however be time bound. Technology transfer to the less developed

areas of the world, initially the white colonies but by the 1950s globally

would make the cost of Empire prohibitive as the gap was eroded.

Bibliography

https://hilary2018.conted.ox.ac.uk/blocks/oxref/index.php?redirect=oxscholar&dest=%2Fview%2F10.1093%2Facprof%3Aoso%2F9780198205654.001.0001%2Facprof-9780198205654-chapter-12. Kubicek, R in The Oxford History of the British

Empire Vol : the Nineteenth Century

Geoffrey

Parker, The Military Revolution, Military Innovation and the Rise of the West,

1500–1800, 2nd edn. (Cambridge, 1990).

What beliefs and arguments drove the movement to abolish

slavery, and what kind of evidence against the slave trade was presented to the

British public?

- ·

Governance and Trusteeship

- ·

Economic

- ·

Strategic

- ·

Evangelical and Humanitarian

Burke and others, perhaps

inspired by the American rebellion, argued that possession of Empire and power

brought obligations to promote the welfare of its peoples. As much concerned with the ability of power

to corrupt the British themselves and seeking thereby to limit that power, by

1783 Burke was speaking in Parliament of the ‘natural equality of mankind at

large’[i] an

admission that slavery and servitude were not compatible with British values. Adam Smith argued against the institution of

slavery as it was economically unsustainable pointing to the inevitably

decreasing productivity of the West Indian monoculture dependent on the Slave

trade and protected by trade barriers. Smith’s

claim that overseas plantations represented much less secure investments than

metropolitan agriculture or industry was confirmed by the British West Indies’

difficulties during the War of American Independence.[ii]

[i] Porter

The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume III: The Nineteenth Century.

Trusteeship, Anti-Slavery, and Humanitarianism Andrew Porter

DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205654.003.0010

What were the main causes of British decolonisation?

Britain was forced out of India and Burma by political change within India, in part a response to the growing demands of the colonial state, in part an outgrowth of both religious revival and new cultural movements. From 1920 the Indian National Congress aimed at destroying the habit of deference to British authority. The arrest of Congress members during the war allowed the rise of the Muslim League. Even before the war there were strains on the system but the need for resources to defeat Germany and, in 1942, Japan’s invasion of Malaya then Burma led to the eventual British commitment to giving India self-government at the end of the war (though the intention was to tie India closely to Britain). In the second half of the war, the causes of mass grievance and fear also grew quickly the likes of inflation and then food shortages (up to 2 million deaths in the Bengal Famine) exacerbated Congress’s calls for independence.

Once the war ended the British were exhausted. Many British officials and soldiers longed to go home and get back to civvy street. Unrest in the Bengal Navy led to fears that the huge Indian Army might mutiny and it was recognised by Wavell and Attlee that if the Congress chose to make trouble, there was little the British could do: ‘I doubt whether a Congress rebellion could be suppressed,’ wrote the Viceroy’s adviser on internal security. Attlee’s own assessment was:

a) In view of our commitments all over the world we have not the military force to hold India against a widespread guerrilla movement or to reconquer India

b) If we had, public opinion especially in our party would not stand for it

c) It is very doubtful if we could keep the Indian troops loyal. It is doubtful if our own troops would act.

d) We should have world opinion against us

e) We have not the administrative machine to carry out such a policy British or Indian.

The end of the Raj did not lead to the immediate break-up of the empire. But it marked a critical break in its internal cohesion, and an irreparable loss of the vital resources – military above all. Still an imperial mentality was still deeply entrenched at all levels of British society (and remains in today’s Tory party). The USA’s hostility to European Empires was tempered by her fear of communism filling a possible vacuum, so for the next few decades the US would continue to accept imperial pretensions, though on its own terms. This harnessing of empire to the task of Cold War containment would extend its life.

Britain’s strategic disasters in 1940–42 marked a momentous change. Canada, Australia and New Zealand (though not South Africa) discovered their strategic dependence on American power. Their status as sovereign countries, became increasingly real, indeed Australia recalled her ground troops from North Africa (despite Chuchill's pleas) to defend the homeland in 1942; they did not return. Canada’s Navy was instrumental in the defeat of the U boat threat in the North Atlantic and by the end of the war she had a rising friendly power on her southern border that offered markets far easier to access than the earlier imperial ones – access to which was made easier by Canada’s being a ‘dollar’ rather than Sterling Economy.

From the late 1940s the pressing issue for Britain became the economy and the weakness of sterling. The reliance on ‘dollar’ goods led to an iniquitous policy of Britain sweating her remaining colonial assets by the transfer of colonial export dollar cash flows from the colonies to London’s ‘dollar pool’, to be spent as London decided a policy one would argue almost specifically designed to cause resentment of Empire as those countries whose currency was tied to sterling – including Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – were forced to accept central control of their dollar spending, and buy sterling goods whenever they could.

By the late 1950s the aggressive expansion of the colonial state – regulating, restricting, conscripting – and the arrival of more and more whites as farmers, miners, officials and experts aroused ever-increasing resentment among African peoples, not least among the traditional chiefs on whom the colonial apparatus relied. De Gaulle’s granting of independence to most of France’s African possession and the collapse of Belgian authority (self-inflicted for a large part) in Congo further inflamed African nationalists and opened the door to Soviet approaches as partner of choice thus further reducing British influence – particularly apparent in Egypt but also elsewhere on the continent.

Continued economic weakness into the 1960s and 70s, and the humiliations of Suez and De Gaulle’s ‘non’ to EEC membership would undermine Britain’s great power pretensions and reduce support at home for further expenditure on an increasingly anachronistic project.

World War 1: Lessons and Legacy of the Great

War. Future Learn MOOC run by University

of New South Wales; Lead Educator - Dr John Connor; Course Educator - Dr Liana

Markovich

The course is presented in three parts:

1 An overview of the War. Concentrating on the conflict on the Western Front and the development of trench warfare.

2 The ‘learning curve’ - compares how the British, French and German armies attempted to end the stalemate of trench warfare by developing new technology, training and tactics.

3 Remembering the First World War explores how the social and political landscape has shaped and changed the memory of the War over the last century, and how art, poetry and novels have contributed to that understanding.

Glossary - International Encyclopedia of the 1st WorldInternational Encyclopedia of the 1st World Warr

Week 1 examines the immediate origin of the War including those alliances that pressed Nations to act. It also looks at the Strategies employed throughout the war by the Germans, British and French. The Germans tried five separate strategies to win the first War and each of them failed:

1. Schlieffen Plan (Moltke) 1914

2. Knockout Russia – negotiated Peace to free Army to attack France unhindered by Eastern Front (Falkenhayn) 1915

3. Bleed France Dry – Verdun (Falkenhayn) 1916

4. Unrestricted Submarine Warfare (Hindenburg/Ludendorff) 1917

5. Kaiserschlacht – defeat Britain and France before US power applicable (Hindenburg/Ludendorff) 1918

Germany’s key strengths were in operations and tactics but her key weaknesses were in logistics and resources, her seizure at the start of the war of much of France’s Iron and Coal industry relieved to some extent here resource issues and also drove French Strategy to the attack in order to recover these. A further problem for Germany, that worsens as the war progresses is the weakness of her key ally – Austria whom she increasingly needs to prop up.

The origins of the War are complex but as is commonly known the spark that ignited the War occurred on 28 June 1914 when the heir to the Austrian Throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo. A month later Austria invaded Serbia, Russia, seeing herself as the defender of Serbia mobilised her army which prompted Austria’s ally Germany to declare war on Russia. Fearing that France would come to the aid of her own ally (Russia) and believing the British, though with an ‘Entente Cordiale’ with France, would remain aloof, the Germans put into to operation the Schlieffen plan in order to defeat France before turning her whole attention to the defeat of the slow to mobilize Russians. As we now know, the German defeat at the Marne ended their chance of defeating France and led to the Race for the Sea and the solidification of the Western Front. Until 1918 further offensives would be a frontal attack against increasingly complex trench systems, in which the odds favoured the defenders. The army commanders always knew that the war would only be won once manoeuvre returned to the battlefield but they lacked the technological means to achieve this.

British Strategy:

The British Army on the First World War is really three different armies:

1. Regular Army BEF of 1914 – Old Contemptibles – small but professional 2 x Corps

2. New Army – Volunteers plus Colonial divisions

3. Conscription 1916 onwards - this is the army which plays probably the biggest role in defeating the Germans on the Western Front.

By 1918, for the first time in history, Britain is a military power. We must remember that Britain did not see itself as a military power. It was the world's biggest financial and naval power – which directed her strategy to win the war by Blockade and by financing her allies – much as she had done during the Napoleonic Wars. By 1917 however, the army is required to do most of the fighting as the French Army had suffered horrendous casualties and was in a state of mutiny. In 1918, Haig deployed the largest field army Britian had ever had and it was this army that was largely responsible for the battlefield defeat of Germany in the 100 days after the battle of Amiens

French Strategy:

In 1914 it was assumed that the only possible way to defeat a German invasion was, in fact, to attack them hence Plan XVII – which actually fell right into the German plan by assisting encirclement! However failure of Plan XVII was a godsend (at horrendous cost) in that it forced the French into retreat upon internal LOCs and eventually into the right place – The Marne. Joffre, unlike Moltke, kept his head and was able to defeat the Germans on the Marne

The French strategy in 1915 was set by political and Allied considerations. At the end of 1914, once the Battle of the Marne had been won and the Germans had been stopped, yet again, at the First Battle of Ypres, it was obvious that the defensive battle had been won. However, German troops still sat in most of-- practically the whole of-- Belgium, and they occupied the mineral-rich industrial areas of northern France. Therefore, for political reasons, the strategy for 1915 could only be that the Germans had to be attacked and driven out of France leading to the strategy of offensive action. A second consideration was the Allies. Russia had done what it promised by attacking Germany in eastern Prussia. So to help Russia the only strategy that was possible in Joffre's mind was on offensives. In fact this was to be the French strategy throughout the conflict though Joffre and more than one successor would be sacked for its failure long before the war’s end.

The course then spends time looking at the Western allies and their differences (including historical enmities) – often leading to misunderstandings. The French saw the British as ‘Germanic’, greedy and arrogant; the British saw the French as being ‘Latin’, emotional and unreliable.

It was Germany’s increasingly aggressive policies in the early 1900s that brought the two nations together. In 1904, France and Britain settled their colonial disputes with the agreement known as the Entente Cordiale. The two countries began joint military discussions that led to agreements that, in the case of war with Germany, the French Navy would take responsibility for the Mediterranean Sea, the Royal Navy for the Atlantic and the North Sea, and the British Army would provide a small expeditionary force to serve beside the French Army.

During the war French political and military leaders argued that France was doing more fighting and suffering more casualties than the British. There was some truth in this in the first part of the war while the British in this period had only a few divisions on the Western Front. By the end of the war, and after horrendous French losses the British having by now become a military power (see earlier) this view could not really be uphold logically.

The French accused the British – whose economy had not suffered from enemy invasion and occupation – of using the war to gain economic advantage though they never fully understood the British contribution to the alliance at sea and financially. So while the British and the French were the chief partners in the alliance that defeated Germany, but there was ‘no solution to the conflict’ between the two nations on how the war should be conducted and how the sacrifices of war should be shared.

Conclusions to Week 1:

The idea of the First World War as a futile and pointless war seems to have come from a viewpoint that the end result in no way justified the huge loss of life. However, European governments did not become involved in the war by accident, but through real commitment to underlying principles of loyalty to allies, the defence of small nations, as well as the opportunistic idea that a war at this time would be to one’s advantage. Certainly at the time war was perceived an instrument of foreign policy – something that its eventual cost would make more liberal nations renounce (though not Hitler’s Germany of course)

These factors drove the strategies of the major powers. Germany supported its ally Austria-Hungary in its declaration of war with Serbia – in today’s terms a state sponsor of terrorism! They believed this would remove the threat to the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian state from rising Slav nationalism. As Russia saw itself as the protector of Serbia, the Germans recognised that supporting Austria-Hungary against Serbia would likely lead to war with Russia. The German Government believed war with Russia was inevitable, and that it was better to take the opportunity to fight the war sooner rather than later. Russian economic growth and the modernisation of the Russian army would, over time, make it a more formidable enemy.

France became part of the war because Germany attacked her Britain had no formal alliance with any European power, but the British Government had held secret military talks with France which did include plans for a small British Expeditionary Force to go to France in the event of a war with Germany. However it was the German invasion of Belgium on 4 August that brought Britain into the war. Though Asquith wrote in a letter on 2 August that his government did ‘have obligations to Belgium’, he also stated that he ‘cannot allow Germany’ to have naval bases on the Belgian coastline as they would threaten Britain – with echoes of the ill-advised Battleship building programme engaged in by Tirpitz. The British declaration of war was therefore a combination of national self- interest and defending the right of Belgium to exist.

What factors worked against mutual toleration between

Catholics and Protestants between the mid-sixteenth century and the end of the

nineteenth century?Britain ,

France and briefly in the USA Bismarck Europe conflict between Lutheran’s and Catholics was

ended by the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 which established the principle that the

religion of the ruler was to be the religion of the state. In spite of this pragmatic approach,

religious differences between Catholics and Protestants would do create violent

conflict in the French Wars of Religion up to the accession of Henry IV in 1598

and later in the thirty years war that was ended by the Peace of Westphalia in

1648. England ’s

own civil war has been described as a religious war however, if this was a

religious war it was between Protestant sects (except in Ireland England Elizabeth Elizabeth France England Britain

and France saw subversion in

religious diversity, it should be noted that the Netherlands Britain Britain , although

in the 1870s Bismarck America

was evident in events such as the attack on a convent in Boston USA England a lack of significant Protestant

minorities in Italy , Spain and Portugal

meant that there was no real significant degree of state sponsored Anti-Protestantism

in these countries, whilst the Treaty of Westphalia had extended the toleration

agreed between Catholics and Lutherans at Augsburg France Britain

there was no formal treaty guaranteeing Catholic rights – in fact after 1678

the Test Acts limited freedoms whilst the Glorious Revolution of 1688 led to a

still permanent settlement whereby Catholics are to this day prevented from

marrying or becoming the Head of the State of the United Kingdom Britain and Europe

suspicion of religious minorities was not uncommon throughout the period. The religious wars of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries were followed by colonial wars in the mid eighteenth

century between Protestant Britain and Catholic France. From 1776 France

supported the rebellious American colonies against Britain

in the war of Independence France Britain Ireland Ireland England

Chidester,

D. (2000), Christianity, Penguin,

London

MacCulloch,

D. (2009), A History of Christianity,

Allen Lane, London

Reynolds,

D. (2009), America, Empire of Liberty: A

new History Allen Lane.

Wolffe, J (2008), AA307 Religion in history: conflict, conversion and coexistence Study

Guide 3, The Open University

AA307 Religion in history: conflict,

conversion and coexistence CD3, The Open University

[1] Quoted in

Wolffe, J (2008), AA307 Religion in

history: conflict, conversion and coexistence Study Guide 3, The Open University

[2] Chidester, D. (2000), Christianity,

Penguin, London

Written 2004

This

essay will examine the nature and dimensions of US

Within the USA USA USA again took

up an isolationist position, which contributed significantly to the failure of

the League of Nations as a security

institution. Its entry into world war

two and its subsequent multi-lateral engagement in the international system

have brought it to pre-eminence. The

position of the USA has come about as a result of its victory in world war two

and its then military (until the mid 1950s it was the only nuclear power) and

economic strength vis a vis its strategic partners in Europe after 1945 and its

eventual ‘victory’ in the Cold War as a result of the economic collapse of the

USSR. From a realist perspective, it has

achieved its position because it has ‘imposed [its] will on lesser states

and…because other states have benefited from and accepted [its]… leadership’

(Gilpin, 1983, p 145.)[2]

From a liberal viewpoint the USA US

The political power of the USA USA USA USA USA USA USA

From a Marxist perspective, US USA USA

The export of Americanism (mass production,

consumption and consumption of culture) to Europe

and beyond has been seen as some (Bromley, 2004, p147)[5],

as a compelling source of US power reshaping the world (Gramsci, 1971, p317)[6].

Given the very different social systems in Europe Americanism is only part of

the story accounting for the USA Anderson USA

The USA Daytona Beach , Florida US USA

Power

is the ability to obtain the outcome one wants (Nye, 2003)[9]. Within the liberal capitalist system, US United States USA USA France , Germany Russian and China deprived the USA US

As mentioned, the USA USA US US

public opinion was horrified at events in Chechnya

in the 1990s and yet the costs of using military or economic power against Russia were too high for the USA USA Pearl

Harbour , “so, too, should this most

recent surprise attack erase the concept in some quarters that America USA

still has the world largest economy, the states-system is multi-polar with the

EU and Japan already as

major liberal competitors to the USA

and new regional economic powers developing in China ,

Russia and perhaps India

In its

relations with rest of the world, the USA US South East Asia the application of military power is

inconceivable except as providing regional security guarantees to liberal

capitalist states. In Europe, continued

involvement in NATO and the application of soft power to encourage eastward

expansion of NATO and the EU also helps to neutralise regional pretensions to

leadership of France and Germany

When

dealing with Russia , and China the USA Russia , China

and the USA China , Russia and perhaps other are uncomfortable with

the USA ’s unipolar moment

and will try to hasten a multipolar world, the USA

Outside the West, and particularly in the Middle

East, evidence of political rather than informal imperialism is seen in the USA ’s actions in Iraq USA U.S. US

policy in Iraq Iraq USA to achieve its foreign policy objectives

at….low cost ….depend in a large part on whether other powers are inclined to

support or oppose US

The

main threats to the USA USA USA USA cannot

control all the threats to these public goods (Bromley, 2004)[17]

In most cases, therefore, it will be in the interests of other states to work

with the USA USA USA USA U.S.

[1] Brown, W. (2004) A liberal international

order, in Bromley. S et al (2004) (ed) ‘’Ordering the International: History,

Change and Transformation’, London and Sterling Virginia

[2] Gilpin, R. (1983) War and Change in World politics (paperback edition), Cambridge

[3] Nye, J.S.(2003) US Power and Strategy After Iraq

[4] Arrighi, G. (1983) The Geometry of Imperialism (revised edition), London

[5] Bromley, S.(2004) American power and

the future of the international order, in Bromley. S et al (2004) (ed) ‘’Ordering

the International: History, Change and Transformation’, London

and Sterling Virginia

[6] Gramsci, A. (1971) Selections From The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (edited and

translated by Hoare, Q and Nowell Smith, G.),London ,

Lawrence

[7] The Economist Nov 6th 2003

[8] Nye, J.S.(2002) The American National

Interest and Global Public Goods, International Affairs,Vol.78,No2

[9] ibid

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] The Economist Nov 6th 2003

[14]

ibid

[15] ibid

[16] Walt, S. M. (2000) Keeping the World Off Balance: Self Restraint and US Foreign Policy,

Faculty Research Working Papers Series No.00-013, Cambridge, Mass., JFK School

of Government, Harvard University

[17] Bromley, S DU 301 Audio

5, The Open University

Sovereignty is the right that a nation claims to rule its

own territory and to be recognised as sovereign over that territory both by

other states and its own citizens.

Autonomy is the capacity of the state to effectively exercise its

sovereignty within its own territory. Autonomy

of the state may be taken to mean either autonomy from external pressure or

from internal pressure. This question

implies that the former meaning is being examined, however it cannot be taken

in isolation as internal pressures will affect policy. In Making the International, Sam Wangwe

states that ‘One consequence of the policy reforms that have been pursued in

Africa under the leadership of the multilateral institutions has been the loss

of autonomy in policy making …of African countries’ Wangwe (2004)[1]. This is not the same as saying that aid

dependence per se reduces autonomy in macroeconomic policy autonomy. I will argue that macroeconomic policy

autonomy is dependent on a number of factors, of which aid is a significant but

not the only one. Many Sub-Saharan African

states have been dependent upon aid since independence and yet had high degrees

of autonomy until after the Berg report of 1981 (World Bank, 1981)[2]

and are now regaining some of the autonomy lost to the Bretton Woods

Institutions (BWIs) in the 1980s and 1990’s.

Until

independence, economic development in Africa was defined by the colonial

authorities. The colonial powers, in the

aftermath of the Second World War used African raw materials to rebuild their

own economies and industries whilst using the colonies as a captive market for

the export of those industries. Macroeconomic

policy can be defined as the measures taken to manage the national economy as a

whole (Mkandiware, 2004)[3]. Upon gaining their independence, African

nations generally followed policies similar to those of India (such as State

participation in industry and import substitution policies) in an attempt to assert

their newly won sovereignty and develop their economies to ‘catch up’ with

those of their previous imperial masters.

Unlike India, African nations generally neglected agriculture and

education whilst remaining relatively open to the global economy.

During this

period of developmentalism, high investment in industrialization and a

favourable global economy with good terms of trade for primary products helped

ensure high levels of growth for most African nations although, there remained

significant differences in the distribution of benefits both within and between

countries. Furthermore the continued

reliance on primary goods export left African states vulnerable to changes in

terms of trade a fact that was compounded by failure to invest in agriculture

leading to a disproportionate amount of export earnings being used for food

imports.

Between 1974 and

the early 1980s, the rapid rise in world oil prices and stagnant or falling

prices for many African export commodities led to severe economic crisis in

most of Africa. It was in these years

that the foundations for the loss of autonomy were laid. In a democratic state the government derives

legitimacy from its electoral mandate.

Most African states at this time were autocratic and derived legitimacy

from economic performance, as economic growth declined legitimacy was

lost. Most governments initially tried to

maintain growth by increasing public expenditure leading to reduced economic

performance and in turn to reduced legitimacy.

From the early 1980s,

African countries under the supervision of the BWIs initiated structural

adjustment programmes designed to move them away from the state-led model

of development which they had followed in the first two decades of independence

towards a fully market-driven system of allocation of resources. The broad

intellectual context for this reform drive was offered by the Berg Report of

1981 which argued that the reason why African economies were in difficulty and were

unable to fulfill their promise was the dominant role of the state in the

political economy. Berg argued the case for African economic policy-making to

shift emphasis towards getting prices right and liberating the forces of the

market in order both to revive exports and improve the incomes of the rural

agricultural populace. His main arguments were taken up by the World Bank which

commissioned his report. It is ironic that at about the same time the

Organization of African Unity (OAU) had adopted the Lagos plan to address the

crises faced by its members. In addition

to retaining the state led model a significant difference in the Lagos approach

was action placing emphasis on adverse external factors, largely ignored in the

Berg report (Olukoshi. A 1999)[4].

Graph 1 – Rate of growth SSA compared with East Asia and

Pacific - note lack of high growth during the adjustment years despite BWI

involvement (From Making the International p 312, original source World Bank)

So far I have

shown that adverse external factors plus omissions from the developmental model

affected the legitimacy, and hence autonomy of African governments to enact

policy. Throughout their history, most

African states have been dependent upon aid – external financing. The key to economic growth is investment

(Athreye, 2004, p212)[5]. With low levels of savings and capital

available within most African states, funds for investment could come either

from exports or from aid. I have already

stated that too much export income was being spent on provision of food. Thus domestic absorption exceeded GDP and

created Trade Gaps throughout Africa. Investment

will be very low or in negative unless it is balanced by foreign currency

received (other than from export because it is less than import) through which

the trade deficit has been financed. Throughout Africa little foreign currency

received comes through exporting labour, or through earning assets owned

abroad, or through inward

foreign direct investment. Therefore, the deficit in availability of foreign currency from trade has been made good mainly by foreign aid in two forms: transfer payments on current account and loans on capital account. Therefore, throughout Africa there is a high dependence on foreign aid.

foreign direct investment. Therefore, the deficit in availability of foreign currency from trade has been made good mainly by foreign aid in two forms: transfer payments on current account and loans on capital account. Therefore, throughout Africa there is a high dependence on foreign aid.

Aid dependence

does not necessarily mean loss of autonomy. Prior to the Berg report, most aid was Project Aid provided

by bilateral agreements. Few conditions were set for the use of aid by donors,

indeed much project aid bypassed government channels, whilst many donors were

less concerned about internal macroeconomic policy than in maintaining the Cold

War balance of power. Furthermore with a

variety of different donors, it was not possible for a single donor to affect state

autonomy in any great way.

By the time of

the Berg Report however, there had been a shift in Western Political ideology

from Keynesian to monetarism. The Berg Report

found western democracies willing to support as its prescription mirrored their

own developing ideologies. As a

consequence donor countries became more willing to act in multilateral terms

with Africa through the BWIs. The

imposition of conditionality, set by the BWIs and supported by donor nations,

upon aid had a major effect upon the autonomy of African states that were

unable to resist donor pressure under aid dependency without causing harm to

their already weakened economies without undermining domestic political

support. During these ‘adjustment

years’ the provision of programme aid was conditional upon the recipient

countries accepting externally set macroeconomic policies. The effects of these free market reforms were

not as expected (see graph 1).

Throughout the adjustment years, SSA GDP growth rates remained

poor. Berg required that Africa should

base its trade on static comparative

advantage. However, the liberalization of import controls led to greater demand

for imports which in turn led to more imports.

At the same time terms of trade for most primary good worsened so that

greater export production failed to bring in correspondingly greater funds the

net result was a widening trade gap, requiring more programme aid.

Disappointed by

the performance of African economies during the adjustment years, Tanzania and

Denmark commissioned the Helleiner report in 1995. Since this report, there has been a retreat

of conditionality upon aid with donor nations seeking to empower African states

to develop their own programmes for aid dissemination. I do not believe that it is mere coincidence

that this phase of recovery of autonomy coincides with the election in the west

of Social Democratic parties during the 1990s.

Dependence on

foreign aid does not automatically translate into loss of autonomy. Much depends upon relations between states

and international donors and on type of aid given and conditions attached to

it. Many states have been dependent upon

aid since independence but have only lost autonomy through the confluence of

worsening global economic conditions, some errors in policy such as the failure

to invest in agriculture, changing types of aid (from project to programme),

problems of state legitimacy in non democratic states with low or negative

economic growth and finally in changing ideologies of donor nations. Nevertheless aid dependency makes a state

vulnerable to interference from external agents and to unrest from within as

aid dependency is symptomatic of weak economies whose legitimacy may be

questioned should economic policy fail to deliver growth.

Part 2 a (435 words)

Assuming that the game indicated in figure 1 is a one shot game;

it is possible to use Nash equilibrium analysis to identify the preferred

options of each player given the strategy of the other player. It is not possible to identify the outcome of

the game however. A Nash equilibrium is a set of strategies, one for each

player, such that, given the strategy of the other player no player can improve

on their payoff by adopting a different strategy (Mehta and Roy, 2004, p 436)[6]. The Nash equilibrium indicates each party’s

best response to the action of the other.

USA

|

|||

Abide by Kyoto deal

|

Don't abide by Kyoto Deal

|

||

EU

|

Abide by Kyoto deal

|

2,2 Preferred outcome to weak play

|

0,4 Nash Equilibrium

|

Don't abide by Kyoto Deal

|

4,0 Nash Equilibrium

|

-6,-6 Catastrophic Play

|

|

Figure 1 Matrix depicting

global warming as a collective action problem game between 2 actors

Analysing the game from the point of view of the EU, if the

USA acts tough and fails to abide by Kyoto, the EU’s best reply is to act weak

and abide as 0 is better than -6; if the USA acts weak and abides by the

agreement, the EU’s best reply is to act tough and not to abide as 4 is better

than 2. From the perspective of the USA,

if the EU acts tough and fails to abide by Kyoto, the USA’s best reply is to act

weak abide as 0 is better than -6; if the EU plays weak and abides by the

agreement, the USA’s best reply is to act tough and not to abide as 4 is better

than 2. These strategies show 2 Nash

equilibria (see figure 1) each cell indicating strategies that are best replies

to each other.

The game being played is CHICKEN. The defining characteristics of Chicken are:

•

The presence of a tough

and a weak strategy.

•

2 Nash equilibria.

•

The players preferred

Nash equilibria outcomes differ – in the example above each player would prefer

to score 4 whilst the other player scores 0.

•

Each player would

prefer the non-equilibrium outcome to the outcome where they act weak – in the

example above each player would prefer to score 2 rather than 0.

In this game neither player would regret their strategy if

they had played their part in reaching one of the Nash equilibria (they could

not have improved upon the outcome given the strategy of the other player). However, before the event it is not possible

to determine which play will occur, it is even possible that the catastrophic

strategy might occur with both actors playing tough as there

is no dominant strategy in Chicken; “Chicken can model a situation where two

actors are confronted with different preferences about a subject, and have

incentives to assert themselves. Therefore, it is often used as a model

of political conflict.” [7]

Part 2 b (728 words)

The newspaper